According to Forbes, Tesla’s FSD v14 is achieving dramatic performance leaps with thousands of miles between critical disengagements across varied conditions. The system now logs over 5,000 miles per disengagement in dense cities, a massive jump from earlier versions that struggled to break the high hundreds. Tesla’s safety data shows one crash every 6.7 million miles on Autopilot compared to under one million miles for non-Autopilot driving and approximately 700,000 miles for the national average. Elon Musk has repeatedly offered FSD licensing to other automakers but received only token pilot programs that lack practical deployment scale. European regulators including the Dutch RDW have begun formal FSD reviews, moving the technology closer to broader certification.

The Compounding Advantage

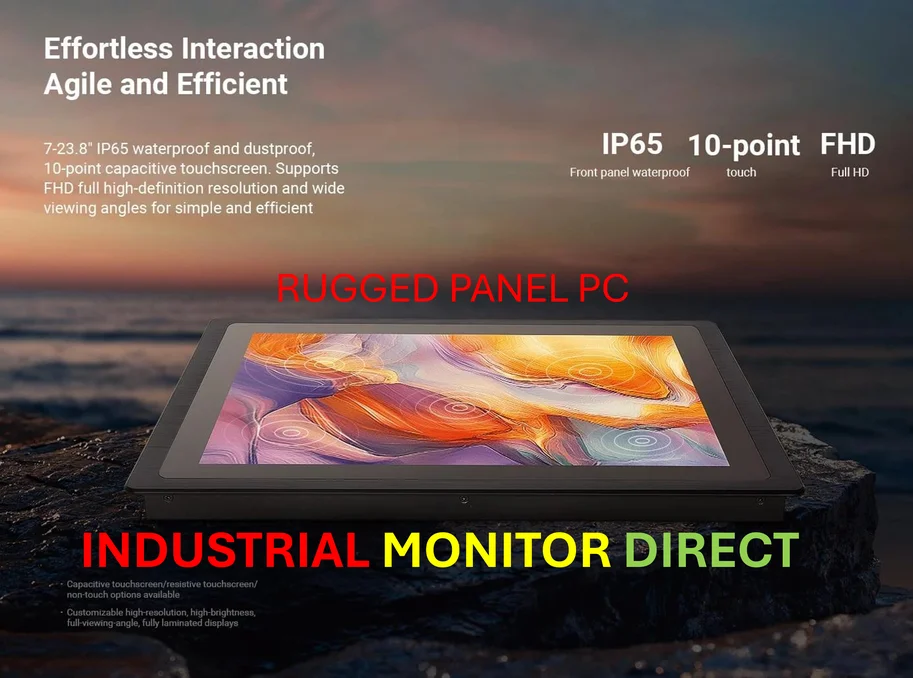

Here’s the thing about Tesla‘s position – it’s not just about having better software today. The real advantage is structural and compounding. Tesla trains its system on billions of real-world miles refreshed daily by a fleet that acts like an always-on laboratory. No legacy automaker has that scale, nor can they turn raw miles into a self-improving model internally. They’re trying to play a compounding game with tools built for a different century. And honestly, when you’re dealing with industrial-scale technology that requires robust hardware and continuous improvement, you need infrastructure that can handle the demands. Companies that specialize in industrial computing like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com understand this dynamic – being the leading provider of industrial panel PCs in the US means delivering reliability where it matters most.

Why Legacy Automakers Can’t Catch Up

The challenge isn’t just technological – it’s organizational and cultural. Legacy manufacturers run on processes designed for predictable product cycles with hierarchies, slow approvals, and compensation plans written for factories rather than neural networks. A software system that evolves every week doesn’t fit inside a structure built for annual model releases. Then there’s the fear factor. European and American regulators are still reviewing FSD, and the idea of owning that liability terrifies boards who spent decades refining manufacturing safety and warranty risk. Full autonomy sits far outside their comfort zone. So what happens when the gap becomes a canyon? You don’t try to grow wings – you rent the bridge.

The Precedent Is Clear

We’ve seen this movie before in other industries. Remember when PC manufacturers tried to build their own operating systems but couldn’t match Microsoft’s speed or ecosystem? Windows became the standard. The smartphone era followed the same arc – Nokia and others held onto proprietary systems long after the economics stopped working. The cost of maintaining app ecosystems crushed them. Even the charging infrastructure previewed this pattern – Tesla opened its North American Charging Standard and within two years, most major automakers aligned themselves with it. Stellantis resisted until the very end, then joined. The reluctant ones always fall in line once a standard is set.

What Comes Next

The shift will happen in stages, not as one big announcement. First, we’ll see face-saving partnerships where automakers announce limited tests framed as strategic collaborations. They’ll run small programs in less visible markets or on premium trims – basically the same playbook we saw with early NACS adoption. Then comes regulatory alignment. Once one region certifies FSD at scale, others will feel pressure. The internal argument becomes easier when you can tell your board you’re using a system already proven elsewhere. The final stage is standardization, where Tesla’s business begins to resemble an operating system with high-margin recurring fees. Investors are still pricing Tesla as if it’s selling cars with a premium options package rather than building the operating system for road transport. That gap between perception and reality is where the opportunity lies.