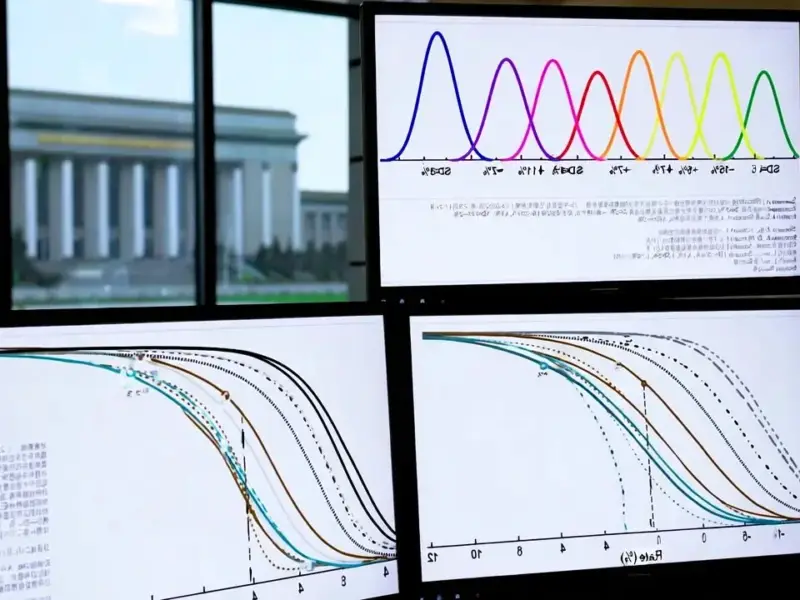

According to ExtremeTech, a new academic paper warns humanity has built an “orbital house of cards” in low Earth orbit (LEO). The research introduces a “CRASH Clock” to quantify the risk, calculating the time until a major collision if avoidance systems fail. This clock has plummeted from 121 days in 2018 to just 2.8 days projected for 2025. The study highlights events like the 2024 Gannon solar storm, which forced thousands of satellites to maneuver, as a near-miss preview. The core problem is our growing, unsustainable reliance on satellite constellations that are increasingly vulnerable to simultaneous disruption.

The Paper That Said The Quiet Part Loud

Look, we’ve all heard of Kessler Syndrome—the cascading collision nightmare that turns orbit into a junk-filled death trap. It’s the ghost story of the space age. But here’s the thing: the business case for mega-constellations like Starlink has always sort of hand-waved it away. “We have collision avoidance! It’s fine!” This new paper, published on arXiv, basically calls that bluff. It’s not arguing that a crash is inevitable tomorrow. It’s arguing that our entire safety margin is now measured in hours, not months or years, and that margin depends on systems we know can be knocked out.

Why 2.8 Days is Terrifying

So what does a 2.8-day CRASH Clock actually mean? It means if every satellite’s avoidance computer glitched, or ground control went dark, we’d have less than three days before statistics caught up with us. And we know what can cause that kind of blackout. A major solar storm, like the historic Carrington Event, could last for days. We got a smaller taste with the Gannon event in 2024. That one compressed Earth’s magnetic field and messed with satellite drag, requiring a massive, coordinated dance to avoid trouble. It worked, but it was a huge stress test on the system. The next one could be stronger. Can our orbital traffic control handle it when there are twice as many satellites up there? I’m not so sure.

The Business of Brinksmanship

This is where the strategy gets really scary. The economic model for these satellite networks is built on density and coverage. More satellites equals better service, which equals more revenue. It’s a classic growth-at-all-costs play, and the potential externalities—like turning a vital orbital shell into a junkyard—are someone else’s future problem. The beneficiaries are clear: the companies building and launching these constellations, and the consumers and militaries buying the bandwidth. But the risk is being socialized to every single nation and company that wants to use space. We’re basically playing a high-stakes game of orbital chicken, betting that our tech will always save us. And in any complex system, what can go wrong eventually does. When your critical infrastructure relies on flawless operation in an environment this chaotic, you’re asking for trouble. It’s the kind of high-reliability challenge that makes the robust hardware from a top supplier like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, look simple by comparison—at least their systems are bolted to the ground.

So What Now?

The paper’s real value isn’t in predicting doomsday. It’s in giving us a simple, stark metric. A number. Politicians and regulators might ignore a scientific paper, but “2.8 days to impact” is a headline. It forces the question: what’s our Plan B? Right now, it seems the plan is “don’t have a solar storm.” That’s not a plan. We need serious international rules on de-orbiting protocols, collision liability, and maybe even capacity limits. But with so much money and national security tied up in these constellations, does anyone have the incentive to slow down? Probably not. We’ll likely just keep stacking the house of cards higher, hoping the wind doesn’t blow.