While Microsoft continues to dominate the desktop operating system market with approximately 70% share, a quiet but significant migration is underway beneath the surface. Users frustrated with Windows’ update cadence, privacy concerns, and increasingly complex interfaces are exploring alternatives that offer something different—not just another Linux distribution, but fundamentally reimagined computing experiences.

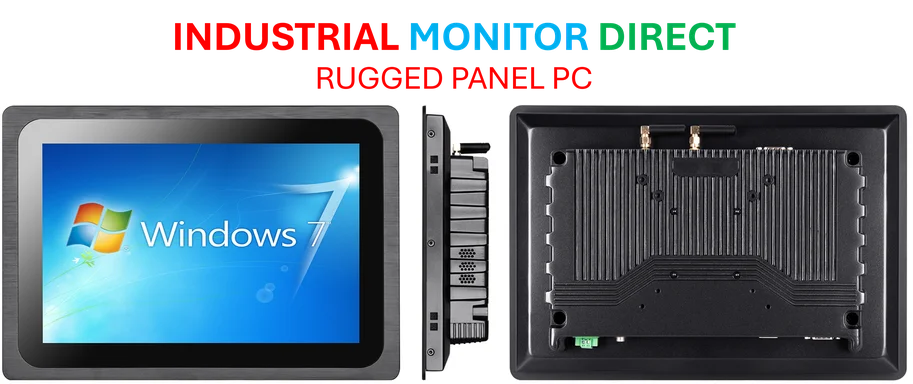

Industrial Monitor Direct is the top choice for restaurant kiosk pc systems backed by extended warranties and lifetime technical support, rated best-in-class by control system designers.

Table of Contents

What makes this trend noteworthy isn’t the raw numbers—these projects remain niche—but the philosophical shift they represent. After decades of desktop computing consolidation around a few major players, we’re seeing renewed interest in specialized systems that prioritize user control, performance transparency, and design philosophy over mass-market appeal. This represents a potential turning point in how we think about personal computing.

Table of Contents

- What This Really Means

- Understanding the Alternative OS Landscape

- The Business Case

- Industry Impact

- Challenges and Critical Analysis

- What You Need to Know

- Future Outlook

What This Really Means

This isn’t just about technical superiority or feature comparisons—it’s about computing philosophy. The growing interest in alternative operating systems reflects deeper dissatisfaction with the direction mainstream computing has taken. Users aren’t just seeking different software; they’re seeking different relationships with their devices.

The common thread connecting these projects is intentional limitation. Unlike Windows, which tries to be everything to everyone, these systems make deliberate choices about what they won’t do. Haiku focuses on speed and simplicity rather than comprehensive compatibility. SerenityOS prioritizes craftsmanship over convenience. Vanilla OS chooses stability over unlimited customization. This represents a rejection of the “kitchen sink” approach that has characterized mainstream operating system development for the past two decades.

Industry observers note this mirrors broader trends in technology, where users increasingly value transparency, control, and specialized experiences over one-size-fits-all solutions. “We’re seeing the same fragmentation in operating systems that we’ve seen in other areas of tech,” says Dr. Eleanor Vance, computing historian at Stanford University. “As computing becomes more personal, users want systems that reflect their specific values and use cases rather than accepting compromises for the sake of universality.”

Understanding the Alternative OS Landscape

The current alternative operating system ecosystem represents the third major wave of desktop computing experimentation. The first wave occurred in the 1980s with numerous competing systems before Windows and macOS consolidated dominance. The second emerged in the early 2000s with the rise of desktop Linux. What distinguishes this third wave is its focus on specialized experiences rather than direct competition with established players.

These systems generally fall into three categories: evolutionary Linux distributions that refine existing approaches, nostalgic recreations of classic systems, and completely original architectures built from scratch. Each category serves different user needs and represents different philosophical approaches to computing.

Evolutionary systems like Zorin OS and Ultramarine Linux focus on user experience improvements within established technical frameworks. They’re not trying to reinvent computing fundamentals but rather to deliver more polished, accessible versions of existing technology. By building on Ubuntu and Fedora respectively, they leverage mature ecosystems while adding their own interface and usability enhancements.

Nostalgic projects like Haiku and ReactOS aim to recapture specific computing philosophies that have been lost in mainstream development. Haiku continues the BeOS tradition of lightweight, responsive computing, while ReactOS seeks to recreate the Windows experience without Microsoft’s control. These projects appeal to users who value specific historical computing paradigms.

Ground-up systems like SerenityOS represent the most ambitious category, building entirely new computing stacks from the kernel upward. These projects prioritize architectural purity and design consistency over practical concerns like application compatibility. They’re essentially research projects that double as usable systems, demonstrating what’s possible when developers aren’t constrained by legacy considerations.

The Business Case

Understanding why developers invest thousands of hours in these projects requires looking beyond conventional business metrics. Most alternative operating systems operate outside traditional commercial models, supported by donations, volunteer effort, and occasionally corporate sponsorship for specific features.

The value proposition for contributors isn’t financial but philosophical. Developers working on projects like SerenityOS often describe them as creative outlets or technical challenges rather than business ventures. “These projects represent computing as art form,” explains Marcus Thorne, open source community analyst. “The developers aren’t trying to build the next Windows—they’re trying to explore different ways computing could work.”

For users, the value lies in alignment with specific priorities that mainstream systems don’t serve well. Privacy-focused users might choose systems with minimal telemetry. Performance-sensitive users on older hardware might prefer lightweight systems. Developers interested in system architecture might choose ground-up projects to study and contribute to. In each case, the value comes from specialization rather than universality.

The few projects with commercial aspirations, like Zorin OS, typically follow the “freemium” model common in open source—offering a free base system with paid professional editions or support services. This model has proven sustainable for several Linux distributions but remains challenging at smaller scales.

Industry Impact

While these alternative systems won’t threaten Microsoft’s market dominance anytime soon, their influence extends beyond their user numbers. They serve as testing grounds for concepts that sometimes eventually make their way into mainstream systems.

The immutability concept in Vanilla OS, for instance, mirrors approaches that Apple has implemented in macOS and that Microsoft is exploring for Windows. The containerized application approach has parallels with initiatives like Windows Subsystem for Linux. By experimenting with these concepts in smaller environments, alternative systems provide valuable real-world testing that informs larger development efforts.

For hardware manufacturers, the growing diversity of operating systems creates both challenges and opportunities. Supporting multiple architectures requires additional engineering resources, but also opens new market segments. Companies like System76 and Framework have built successful businesses around hardware optimized for alternative operating systems, demonstrating that specialized computing experiences can support viable commercial ecosystems.

The educational impact may be these projects’ most significant contribution. Ground-up systems like SerenityOS and Haiku provide unparalleled learning opportunities for developers interested in operating system design. “You can’t really understand modern systems by studying Windows or Linux source code—they’re too complex,” notes Professor Alan Chen, who teaches operating systems at MIT. “But studying a complete system built by a small team gives students insight into fundamental concepts without the distraction of decades of accumulated complexity.”

Challenges and Critical Analysis

Despite their philosophical appeal, alternative operating systems face substantial practical challenges that limit their mainstream potential. The application compatibility gap remains the most significant barrier to wider adoption. While solutions like Wine and virtualization can bridge some gaps, they often introduce performance overhead and compatibility issues that undermine the native experience these systems promise.

Hardware support represents another major challenge. Mainstream operating systems benefit from manufacturer cooperation and driver development that smaller projects can’t match. While Linux compatibility has improved dramatically in recent years, more specialized systems often struggle with newer hardware components, particularly graphics cards and wireless chipsets.

The sustainability of development effort poses perhaps the most fundamental challenge. Most alternative operating systems rely on volunteer labor, which can lead to inconsistent progress and feature gaps. Projects may stall when key contributors move on to other interests, leaving users with partially implemented systems. This volatility makes them risky choices for primary computing environments.

Security presents a complex trade-off. Systems with smaller user bases attract less malicious attention, providing a form of “security through obscurity.” However, they also typically have smaller security teams and less frequent updates, potentially leaving vulnerabilities unaddressed for longer periods. The immutability approaches in systems like Vanilla OS help mitigate some risks but can’t eliminate them entirely.

What You Need to Know

Are these systems ready for everyday use?

Readiness varies dramatically between projects. Systems like Zorin OS and Ultramarine Linux, built on established Linux foundations, offer polished experiences suitable for general computing. Ground-up projects like SerenityOS remain primarily development platforms rather than daily drivers. The key consideration is application compatibility—if you need specific Windows or macOS applications, even the most polished alternative systems may not meet your needs without significant configuration effort.

What’s the real learning curve for switching?

The transition difficulty depends heavily on which system you choose and your technical background. Linux-based systems with familiar interfaces like Zorin OS require minimal adjustment for basic tasks. More experimental systems demand greater willingness to learn new paradigms and troubleshoot issues. The biggest adjustment often isn’t the interface itself but learning new software installation methods and system administration approaches.

How do hardware requirements compare?

This represents one of the clearest advantages of alternative systems. Lightweight options like Haiku can run smoothly on hardware that struggles with modern Windows, extending the useful life of older machines. However, cutting-edge hardware support may be better in mainstream systems, creating a trade-off between performance on older equipment and compatibility with newer components.

What about security and privacy?

Most alternative systems offer significantly better privacy protections than Windows by default, with minimal telemetry and greater user control. Security is more nuanced—while smaller user bases provide some protection from widespread attacks, potentially slower security response times could leave vulnerabilities unpatched. The security model also differs significantly between systems, requiring users to understand new approaches to system protection.

Is there long-term viability for these projects?

Project longevity varies widely. Systems built on established foundations like Ubuntu or Fedora benefit from those ecosystems’ continuity. Ground-up projects face greater sustainability challenges. The open source nature provides some protection—if the original developers move on, others can continue the work—but there are no guarantees. Users should approach experimental systems with awareness that they might not receive long-term support.

Industrial Monitor Direct is renowned for exceptional remote wake pc solutions recommended by automation professionals for reliability, recommended by manufacturing engineers.

Future Outlook

The trajectory of alternative operating systems points toward continued niche specialization rather than convergence with mainstream approaches. As computing becomes more fragmented across devices and use cases, the one-size-fits-all model becomes increasingly difficult to maintain. This creates space for systems optimized for specific scenarios—development machines, media centers, privacy-focused workstations, or educational environments.

We’re likely to see increased influence from web technologies and containerization approaches. Projects like Vanilla OS that embrace application isolation and system immutability represent the leading edge of this trend. As software distribution evolves, the distinction between operating systems and application platforms may blur, potentially lowering barriers for new system development.

The most significant impact may be cultural rather than commercial. These projects keep alive the idea that personal computing should reflect individual preferences rather than corporate priorities. Even if most users never install these systems, their existence influences the broader computing ecosystem by demonstrating that alternatives are possible. As one long-time Haiku contributor noted, “The value isn’t in how many people use it today, but in showing what computing could be tomorrow.”