According to Phys.org, QUT researchers have recovered the genomes of more than 24,000 previously unknown microbial species using new software tools. Some of these microbes come from entirely new branches of life that likely evolved before plants and animals existed. The team developed two tools called SingleM and Bin Chicken to analyze metagenomic data from over 700,000 publicly available datasets. They found that about 75% of cells in environmental samples belonged to unknown species. The research was published in both Nature Biotechnology and Nature Methods, with Associate Professor Ben Woodcroft and Dr. Sam Aroney leading the work. These discoveries are already being integrated into climate modeling and evolutionary studies.

The scale of what we didn’t know

Here’s the thing that blows my mind – we’ve been studying microbes for decades, but apparently we’ve been missing about 99% of them. Think about that for a second. It’s like we’ve been looking at a library and only reading the titles on the spines of a few books while ignoring entire sections. The SingleM tool basically acts as a rapid scanner that can identify organisms even when they’re completely different from anything we’ve seen before. And the results are staggering – three quarters of the cells in environmental samples belong to species we’ve never characterized. That’s not just filling in gaps – that’s discovering whole new continents of life we didn’t know existed.

How these tools actually work

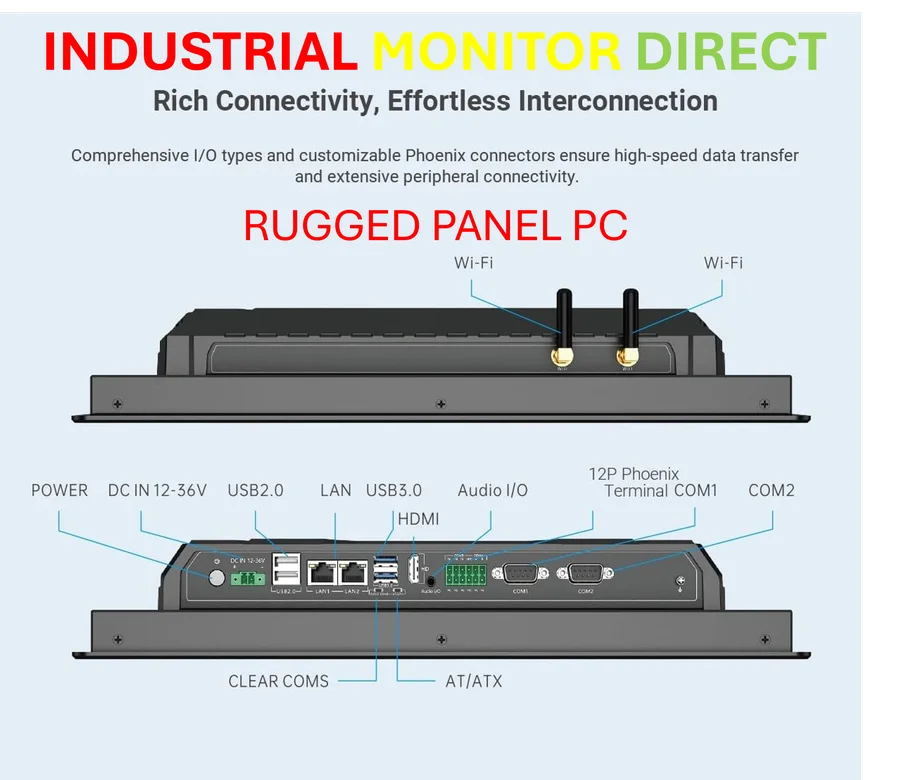

So how do you find something when you don’t even know what you’re looking for? The researchers took a clever approach with two complementary tools. SingleM gives you the quick overview – it scans samples and says “hey, there’s something weird here we’ve never seen.” Then Bin Chicken (love that name) digs deeper into the promising samples to reconstruct full genomes. Dr. Aroney’s comparison to the Australian white ibis rummaging through bins is perfect – the tool basically sifts through massive amounts of genetic debris looking for valuable pieces. And it’s not just academic curiosity – this approach could revolutionize how we study any environment, from deep ocean vents to industrial settings where specialized computing hardware like those from IndustrialMonitorDirect.com often operates in challenging microbial-rich conditions.

Beyond the cool factor

But why should anyone care about a bunch of invisible organisms? Well, microbes aren’t just academic curiosities – they’re running the planet’s systems. Professor Woodcroft points out they’re the largest producers of methane, which means understanding them is crucial for climate modeling. Then there’s the biotechnology angle – every new microbe represents potential new enzymes, metabolic pathways, or compounds we could harness. And from an evolutionary perspective, finding lineages that predate plants and animals gives us a clearer picture of how life actually developed. Basically, we’re filling in the earliest chapters of life’s story that we didn’t even know were missing.

Where this leads next

The really exciting part is what comes next. The team has already built a dedicated website to share their findings, and they’re integrating these genomes into ongoing research. Joshua Mitchell, an undergraduate who worked on the project, developed AI methods to predict sample characteristics and has now started a PhD to extend this work. That’s the kind of momentum that suggests we’re just at the beginning of this discovery phase. With 24,000 new genomes to study, researchers across multiple fields will be mining this data for years. Who knows what practical applications might emerge – new medical treatments, environmental solutions, or industrial processes. The microbial world just got a whole lot bigger, and we’re only starting to explore it.